by Cari Frank, CIVHC’s VP of Communication and Marketing

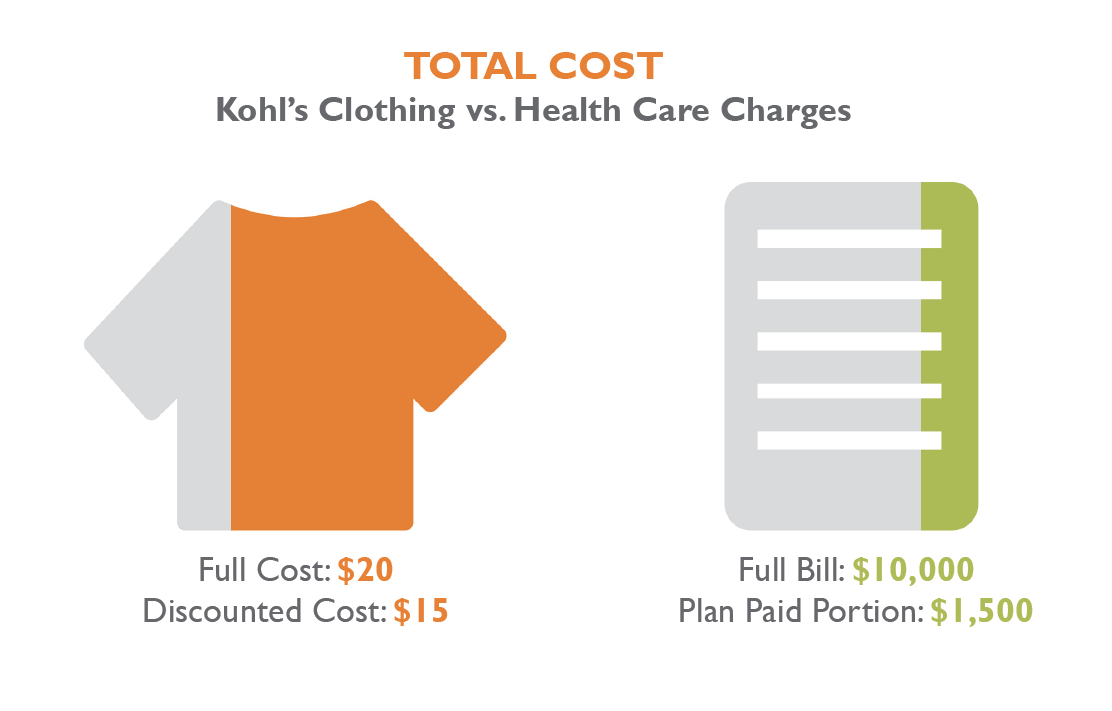

My friend’s father just had surgery to release pressure from an accident that caused swelling in his brain. After the bill arrived, he was shocked that the surgeon billed $10,000 for the surgery, yet only received $1,500 from Medicare. That’s when I had to tell him about the mysterious world of health care charges and how little they have to do with what should or does get paid.

If you’ve ever shopped at Kohl’s, you’ll understand the concept of health care charges. It’s rare to have to pay the full price listed for anything at Kohl’s because part of how they suck you in (myself included) is that everything in the store is typically on sale from what the tag says is full price. You leave feeling like such a savvy shopper because you got 25% off!! Then you realize after shopping there several times that most of the store is always on sale and the full price listed isn’t something they ever expect to get. What’s worse is that what you just bought on sale for 25% off, your friend got for 50% off a few weeks later.

The same basic concept is true for health care services. Providers and facilities set their charges knowing they will be individually negotiating and essentially putting those services “on sale” for health insurance payers who want to do business with them. So, it stands to reason that the higher they set their charges in the first place, regardless of how much it actually costs to provide those services, the more money they might get because the negotiating point is starting out higher. It’s just a better business decision to continually increase charges considering 25% of $10,000 is a lot more than 25% of $5,000.

The same basic concept is true for health care services. Providers and facilities set their charges knowing they will be individually negotiating and essentially putting those services “on sale” for health insurance payers who want to do business with them. So, it stands to reason that the higher they set their charges in the first place, regardless of how much it actually costs to provide those services, the more money they might get because the negotiating point is starting out higher. It’s just a better business decision to continually increase charges considering 25% of $10,000 is a lot more than 25% of $5,000.

In the example of my friend’s dad, the surgeon’s charge was $10,000 and Medicare paid $1,500. Medicare is a different type of health care payer in that rather than negotiating payments based on charges, they set a fee schedule based on what is determined reasonable by an independent advisory group called MedPAC. MedPAC takes multiple factors into consideration when setting payments like how much it should cost to provide the service after considering location (rural vs. urban), type of hospital (teaching hospital, etc.), and how many uninsured and public payer patients the provider serves. The payments they calculate are supposed to be adequate to cover costs for providers and hospitals that run efficiently and don’t have excessive operating costs.

Providers have to accept what Medicare offers to pay or decide not to take Medicare patients, which usually represents a significant number of patients and would be financially detrimental. Commercial insurance payers, on the other hand, usually negotiate rates with providers, and typically do so based on either a percent of the total charge or a percent of what Medicare would pay.

CIVHC recently ran an analysis for the Colorado Business Group on Health (CBGH) that evaluated commercial insurance payments for the top 12 Inpatient and top 10 Outpatient health care services by volume. What we found is that commercial health insurance payments in Colorado vary a lot when comparing payments to what Medicare paid. The data shows that commercial payers are paying between three and five times Medicare rates in some instances. In our example, that would mean some commercial payers would have paid the surgeon $4,500 and some would have paid as high as $7,500 for the same procedure.

We also evaluated potential cost savings scenarios if payments were set at the median statewide commercial payment, or 1.5 or two times Medicare payments. Just for those 22 services alone, by reducing variation we could save $49-$178 million annually in Colorado.

At a recent CBGH meeting, results of the analysis were shared with business leaders, providers, state officials and others. CBGH Executive Director, Robert Smith, argued that employers and payers should start using Medicare as a baseline upon which to negotiate rates since they are determined based on actual costs, as opposed to charges which are set by providers and facilities incentivized to have maximum negotiating power. At the event, Marilyn Bartlett, administrator of the largest self-funded employer for the state of Montana, shared how basing payments on a percent of Medicare saved their state over $100 million in the first year and prevented them from running out of funding to provide coverage to their employees.

Attendees at the meeting were interested to learn about the data presented and the experiences of other states that have addressed rising costs by evaluating Medicare payments as a benchmark. There was interest from Colorado State officials, employers, and the payer and provider community to continue conversations like this to identify ways we might be able to address rising costs in Colorado that are impacting all of us.

![]() On November 13th, CIVHC will be hosting a full day CIVHC Connect meeting to share the results of the analysis along with other new data available from the Colorado All Payer Claims Database. We will also be sharing the Colorado results from the Catalyst for Payment Reform survey conducted this year. Be sure to join our email list so you can reserve your spot when registration is open.

On November 13th, CIVHC will be hosting a full day CIVHC Connect meeting to share the results of the analysis along with other new data available from the Colorado All Payer Claims Database. We will also be sharing the Colorado results from the Catalyst for Payment Reform survey conducted this year. Be sure to join our email list so you can reserve your spot when registration is open.